Actresses Kirstie Alley and Kelly Preston lead protestors in a march against the American Psychiatric Association (APA) on May 19, 2003 in San Francisco.

Earlier this week, I had dinner with a recently retired lawyer who has spent the past 40-odd years working to protect the rights of people with mental illness. She shared with me an anecdote that, she said, had set the course of her entire career:

One day in the summer of 1970, she was working at a St. Louis legal clinic on her law school break, when a 17-year-old girl walked in with her boyfriend. The boyfriend was black. The girl was white — and pregnant. The couple wanted to stay together and raise their baby. The girls’ parents were hell-bent on splitting them apart — and on making sure that they wouldn’t have a mixed-race grandchild. And so, they were having the teenager committed to a mental hospital where they could force her to have an abortion. “There was nothing we could do,” the lawyer told me. “There were no laws we could use to protect her.”

(MORE: What Counts As Crazy?)

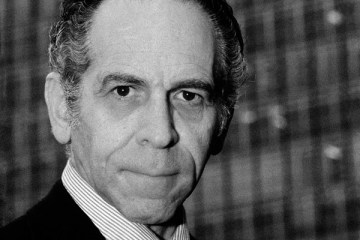

This kind of awful story, in which coercive psychiatric “treatment” was used to punish a wayward teenager, wasn’t so rare when Dr. Thomas Szasz, a professor of psychiatry at SUNY Upstate Medical University in Syracuse, who died last weekend at the age of 92, began to publish books that accused colleagues in his profession of committing crimes against humanity. Psychiatry, Szasz said in books like The Myth of Mental Illness and Ideology and Insanity, was a “pseudomedical form of control.”

“There can be no such thing as mental illness,” he even declared.

In so doing, the Hungarian-born Szasz became the founding father of the American Antipsychiatry Movement, and a hero to many who deplored psychiatry’s often-abusive mid-twentieth century practices. (Among his admirers: the Church of Scientology, with whom Szasz founded the anti-psychiatry Citizens Commission on Human Rights in 1969.) His work inspired the highly influential patients’ rights movement to put an end to the most egregious practices once common in state mental hospitals and remake the entire legal framework around involuntary psychiatric treatment. But he also left behind a legacy of denial of the seriousness of mental illness that has done more damage than good.

(MORE: The Latest Trend: Blaming Brain Science)

David Lees / Corbis

In 1992, Szasz was sued by the widow of another psychiatrist who killed himself while in treatment with Szasz, after Szasz advised him to stop taking the medication he’d been prescribed for bipolar disorder. (The Syracuse Post-Standard later reported that the lawsuit had been settled for an undisclosed sum in April 1994, shortly before it was to be tried in state Supreme Court.)

And in the decades since that event, the Szasz school of thought — which maintains that the extreme distress we see in people labeled mentally ill is nothing more than a form of social protest against unbearable situations—has had an insidious and wide-ranging effect. It has left us with a cultural tendency to both question and romanticize some forms of mental illness — such as depression and ADHD — as higher, more “authentic” states of being. This trick of mind, which denies the reality of suffering and impairment, has kept countless people from seeking help, including innumerable parents who fear that taking their child to a psychiatrist will inevitably lead to his or her being “put in a box” or denatured with drugs.

In addition, the anti-treatment movement Szasz intellectually inspired facilitated the release of tens of thousands of seriously ill mental patients who, when they relapsed, had nowhere to go and no one to help them, and often ended up in prison or living life on the streets. Many mental health advocates today are struggling against the less well-considered aspects of the patients rights movement: working to support families who can’t secure care for their loved ones unless they are dangerously violent or suicidal.

(MORE: What To Make of the New Autism Numbers)

The profession of psychiatry has changed enormously since the time that Szasz began writing, mostly in good ways. Some stigma has abated; the sense of shame that once kept most people from ever speaking of seeing a “shrink” has greatly lessened. But casting doubt on the lived reality of mental illness continues. It’s a newer form of stigma that presents itself as intellectual sophistication. It permeates journalism, in particular, and speaks itself every time we write stories that parse “true” depression (the suicidal kind) from the whiny, self-indulgent, unjustifiably overmedicated, “mild” kind. It comes up every time we trivialize ADHD as a pseudo-affliction of “wiggly boys” or ambitious high school students who want to drug themselves up to get better grades.

This pernicious form of stigma has become second nature for many right-minded people eager to prove their independence from the machinations of the hand-over-fist-money-making drug companies. Yet it’s a form of social protest that, long removed from its valid historical roots, has become simplistic and sometimes even harmful.

It’s time to give Szasz his place in history. And then to move on.

MORE: GlaxoSmithKline’s Fine: Will It Stop Big Pharma Fraud?