“I don’t want you to freak out,” my mother told me one morning when I was 12, “but I think you may have put on a little bit of weight.”

Pick your jaw up from the floor and put away your pitchfork, because this nugget of real talk was one of the best things my mother ever did. Horrified relatives said I would need years of therapy to forgive my mother for “fat-shaming” me into anorexia, that I would eventually turn to drugs and cutting to heal my crippled psyche before I succumbed to a life of crime. None of these things happened. Instead, I have a good relationship with my body and my mother, partly because she told me when I was getting a little plump.

“It’s only 3 or 4 pounds, and it’s not the end of the world,” she said. “It happens to everyone. I’ll help you figure it out.”

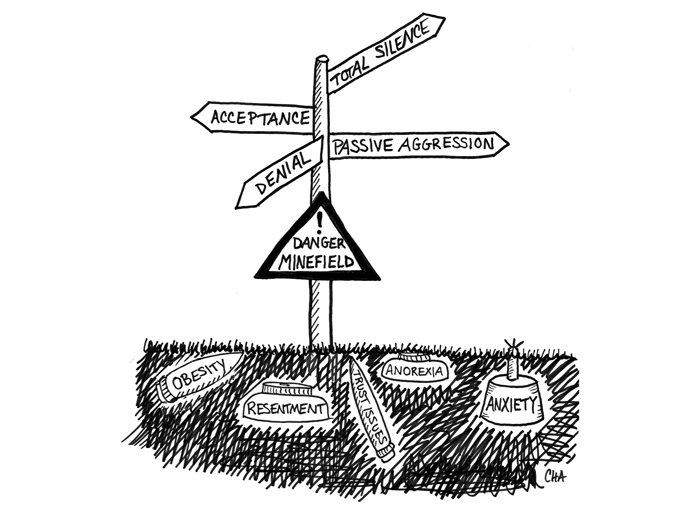

The conversation around young girls and weight is so fraught that many mothers avoid having it altogether, or opt for gauzy platitudes about unconditional love. But girls aren’t stupid, and tip-toeing around the body talk just reinforces the idea that weight is some kind of all-powerful force to be reckoned with, A-Thing-That-Shall-Not-Be-Named. My mother decided to name the demon and teach me how to deal with it, which demystified the weight loss process and made it a lot less scary.

“If your hair was unruly, or if you had missed a button and your shirt was lopsided, I would have told you,” she told me when I asked her about it for this piece. “It’s the same thing.”

In the wake of dozens of “Real Beauty” ad campaigns, and billions of adolescent selfies, everyone’s talking about mothers, daughters, and body image. On Wednesday’s installment of the TODAY Show’s new “Love Your Selfie” campaign, Cameron Diaz and Maria Shriver gathered together moms and girls to discuss how their self-confidence affects one another. “I was taught always from day one that beauty comes from within,” said one of the girls, echoing the schmaltziness that usually surrounds this topic.

Numerous studies have shown that mothers influence their daughters’ self image more than the media does, and some scientists recommend that mothers nix body talk entirely; Dr. Leslie Sim of the Mayo Clinic told USA Today that she recommends “zero talk about dieting, zero talk about weight.” Diaz was urging women to talk more openly about the science of healthy eating, but most people are still uncomfortable with candid discussions of a girl’s actual weight. Just ask Dara-Lynn Weiss, who was practically tarred and feathered for putting her 7-year old on a diet and writing about it in Vogue.

The mystical amulets of “self-love” and “inner beauty” sound nice and progressive, but they’re little comfort during a meltdown in the bathing suit store. And these ephemeral ideas leave girls stranded between two worlds, unsure whom to trust; their mothers who say they’re perfect just the way they are, or a world that tells them otherwise. Eventually it becomes too exhausting to maintain total acceptance of the way we look, and the “self-love” gets drowned in a wave of self-doubt fueled by everything from the media to the kids at school.

Body-image theorists are right that we as a society need to develop a greater acceptance of different body types, but my mother wasn’t concerned with society, she was concerned with me: she noticed that I wasn’t exercising, that my clothes weren’t fitting me right, that I would come home depressed from school dances and look glumly in the mirror. Of course, no middle school girls likes to hear that they’ve gained weight, and I had a good 15-minute tantrum about when she told me, but at that age I would cry when Blockbuster was out of the Titanic VHS.

So after I pulled myself together, my mother and I devised a simple and easy plan: I would cut dessert for two weeks, and run two laps around a small park near our house every day. When I came back sweaty after my first run, she said, “It’s already working!” At the end of the week, she said “you’re looking so much healthier already,” and after the second week, she said “Congratulations! You did it!” The next time I asked her if I looked fat, she said I looked great. And I believed her.

That was the first of many candid conversations with my mother about my weight. She explained that it was much easier to lose 3 or 4 pounds than 10 or 15, and that she would tell me if I was getting bigger so I could make healthy changes before the situation got out of control. That made sense to me, and besides, the psychological effort to maintain a zen-like acceptance of my body was much harder than doing a few sit-ups now and then.

Sometimes I would ask her if I looked big, and sometimes she would tell me I was looking a little “zaftig” or “getting a butt.” I wasn’t thrilled to hear this, but it never sent me into a tailspin. Instead, it was like she had just tasked me with something mildly annoying but doable, like cleaning my room every day. It didn’t feel like a condemnation, it felt like a reality check.

My mother’s strategy might not work for everybody; I’m lucky that I have a medium build, a normal metabolism and am fortunate enough to have access to healthy food. But being frank about weight loss has helped me stay sane about my body even into adulthood. “Everyone has a basic weight equilibrium, sometimes you’ll be above that, sometimes you’ll be below that,” she told me, “but the important thing is to not go nuts about it.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Charlotte Alter at charlotte.alter@time.com