The recently discovered film clip of President Franklin D. Roosevelt being pushed in a wheelchair, despite showing neither Roosevelt’s face nor the wheelchair, has become an object of considerable public interest. One reason people find the clip so fascinating is that it seems to represent a radically different era in American political life—one in which the president could rely on the press corps to help him hide from the larger public something so glaringly obvious as the fact that he was a paraplegic from having contracted polio at age 39.

An NBC Nightly News report on the discovery stated that there was “a gentlemen’s agreement” between FDR and the press corps to hide the extent of his disability, and the Associated Press wrote that it was “virtually a state secret.” That has long been the conventional wisdom, repeated in countless books and articles. But it is inaccurate. In fact, the press sometimes described his condition in great detail.

A 1932 New York Times Magazine profile of the then-Governor of New York described how, at his Hyde Park home, he “wheels around in his chair.” A TIME article from February 1, 1932 said that swimming and exercise “have made it possible for the Governor to walk 100 ft or so with braces and canes. When standing at crowded public functions, he still clings precautiously to a friend’s arm.” Before his inauguration as President in 1933, TIME noted, “Because of the President-elect’s lameness, short ramps will replace steps at the side door of the executive offices leading to the White House.” And a TIME article from December 17, 1934, described a scene in which “bodyguard Gus Gennerich helped the President into his wheel chair, rolled him the length of the West colonnade to the new White House offices.” Another profile, this one in the New Yorker in 1934, stated that “he is almost always pushed to the west end of the White House in a small wheelchair.” Seven years later, on January 20, 1941, LIFE magazine noted that “by 11 o’clock he is up, dressed and on his way in a wheel chair down the long passageway to his office…” (Not that it slowed him down in any way. The headline for the article was “Roosevelt: From Breakfast in Bed to Wisecracks at Movies, President Retains His Bounce after Eight Years.”)

As for incriminating images, it took far more than a “gentlemen’s agreement” for the FDR administration to discourage photos and newsreel film of the president in his wheelchair. Rather, the Secret Service used force. As Editor & Publisher reported in 1936, if agents saw a photographer taking a picture of Roosevelt, say, getting out of his car, they would seize the camera and tear out the film. “By what right they do this I don’t know,” the correspondent wrote, “but I have never seen the right questioned.” A 1946 survey of the White House photography corps confirmed this, finding that anyone the Secret Service caught taking banned photographs “had their cameras emptied, their films exposed to sunlight, or their plates smashed.”

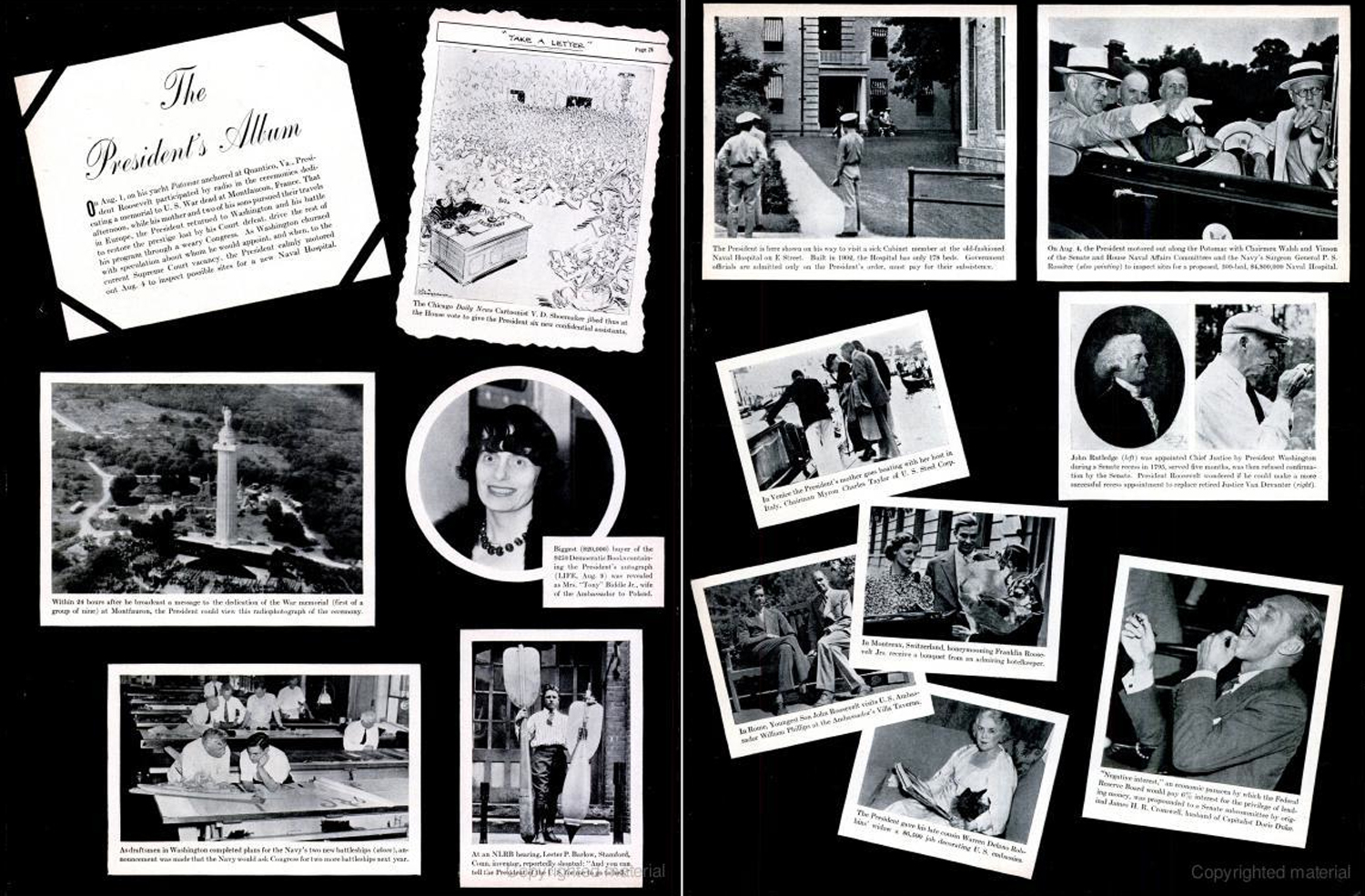

But several of the country’s most powerful publishers—media titan William Randolph Hearst, Time Inc. owner Henry Luce, Chicago Tribune boss Robert McCormick—did not support FDR politically and had no interest in making the President look good. Indeed, in 1937 Luce’s Life magazine disregarded White House rules and published a photo of Roosevelt in a wheelchair. It was shot from a distance, and the figures are not identifiable, but the caption clearly states, “The President is here shown on his way to visit a sick cabinet member at the old-fashioned Naval Hospital on E Street.” Roosevelt’s press secretary was furious and wanted to launch an investigation, as he stated in a memo that is held at the FDR Presidential Library.

August 16, 1937 issue of LIFE Magazine, the photo of FDR in a wheelchair is on the right page on the upper top left.

The misconception that FDR’s disability was a “state secret” guarded by the press has endured for so long in part because there is an element of truth to it. The examples above notwithstanding, mentions of Roosevelt’s wheelchair were extremely rare. Far more commonly, news coverage depicted him as someone who had been stricken by polio but who had triumphed over his affliction—which of course he had, despite the fact that he remained paralyzed. This was the image that FDR and his advisers wished to project, and they largely succeeded.

But the myth has also lived on because of our tendency to romanticize the past as a rosier time—in this case, a time when the press was not out to get politicians, and when leaders were judged on their merits, not on the way they look in a flight suit or whether you’d like to have a beer with them. But as historical research often shows, the past was every bit as complicated as our own time.

Matthew Pressman is a doctoral student in history at Boston University. His article “Ambivalent Accomplices: How the Press Handled FDR’s Disability and How FDR Handled the Press,” will be published this September in The Journal of the Historical Society. The views expressed are solely his own.