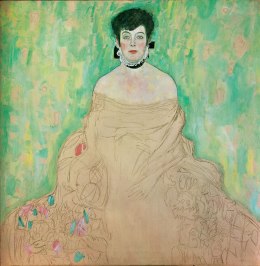

Portrait of Amalie Zuckerkandl by Gustav Klimt

In the past few weeks, a Gustav Klimt portrait hanging in a show at London’s National Gallery was denounced as Nazi loot. A museum director in Vienna resigned in protest over his staff’s ties to a new foundation tainted by Nazi art theft. And a Munich art collector was discovered to be hiding perhaps a billion dollars of stolen art.

Many people were surprised by the flood of revelations, wondering: How can there still be so much stolen art at large, 70 years after World War II?

For decades, the keepers of Nazi-looted art have been biding their time until various statutes of limitations lapsed. They have hidden behind archaic laws that complicate the return of looted works of art to their rightful owners—or have simply refused to investigate red flags that suggest a dubious provenance for a work in their collection.

A 1997 study estimated that some 100,000 stolen pieces of art were still missing. In 1998, 44 nations agreed to create a central public registry of art that might be Nazi loot. Though hundreds of art works have been returned, there has been no stampede of museums, auction houses and collectors eager to comply with the agreement. In much of Europe, laws still tolerate the “grey market” for stolen art.

However, our hyper-viral media landscape has revealed the shenanigans of the art world to a larger and less tolerant audience. Social media is bringing long-overdue claims into the open—and showing there is a long way to go in complying with the moral obligations of restitution.

Take the case of the art stored in a Munich apartment, a cache of more than 1,400 works by Picasso, Matisse, Munch, and Cezanne. From the moment the story broke in November, it went viral on Facebook and Twitter, sweeping across time zones and diverting attention from celebrity news.

Cornelius Gurlitt inherited the drawings and paintings from his father. Some of the work was deemed “degenerate art” and pulled from the walls of German museums in the late ’30s. Some probably belonged to Jewish families. In March 2012, German authorities found the art while investigating Gurlitt for tax evasion but remained silent about the discovery. A German magazine broke the news in early November 2013.

Germany was woefully unprepared to handle the firestorm that ensued. Authorities told an astonished public that they may have to return the stolen art to Gurlitt because the 30-year criminal statute on theft has expired. Unsurprisingly, there have been calls for cases like this one to be considered theft in the service of genocide, under the Nuremberg War Crimes framework.

The ongoing Nazi art theft debacle in Munich may prove to be instructive. The whole world is watching. It is still possible for Germany to confront this moral challenge with grace—and set a dignified example for other countries that may be forced to confront belated Nazi art theft restitutions of their own.

Anne-Marie O’Connor is the author of the award-winning nonfiction Nazi art theft saga, “The Lady in Gold, the Extraordinary Tale of Gustav Klimt’s Masterpiece, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer.” She wrote this for Zocalo Public Square.